Link to the SecuLEx paper: https://orbi.uliege.be/handle/2268/331735.

If you have solar panels, an electric vehicle, or a battery, you are part of a revolution. But this energy revolution is creating hidden problems in the power networks that only a few people see.

At times, there is too much demand when everyone plugs in their electric vehicles after work. At other times, there is too much generation, as solar panels flood local grids with excess energy. In both cases, the network faces some problems, such as congestions and voltage deviations.

When the grid reaches its limits, operators have no choice but to restrict energy flows, either by limiting consumption, forbidding new users to connect to the grid (or with very limited capacity), or curtailing renewable generation. Across Europe, this leads to an estimated €1.5 to €2.5 billion worth of clean energy wasted every year [1].

Evolution of grid management

For decades, the network management strategy was simple: build big and forget about it. This “fit-and-forget” strategy worked when power flowed only in one way: from centralized power plants to consumers.

More recently, operators have started deploying smart, data-driven strategies that rely on real-time measurements to keep the grid secure.

One common approach is active network management (ANM) [2], where the operator dynamically modulates power injections or withdrawals by curtailing solar generation or limiting EV charging, to prevent congestions or voltage issues.

But these methods still depend on centralized, real-time intervention: the operator remains in charge of deciding how and when to act.

What if, instead, customers could coordinate themselves through a market-based mechanism by adapting within secure boundaries without direct operator control?

In our recent research, we introduced SecuLEx (Secure Limit Exchange, [3]). This new market-based system turns grid capacity into a tradable commodity to maximize the value from the already existing infrastructure.

How it works:

Every home or business connected to the grid receives DOEs, intervals indicating the amount of power they can inject or withdraw without stressing the network. This means that wherever the withdrawal/injection is inside the limits, then the network is secure. But instead of being fixed, these envelopes can be traded in a market.

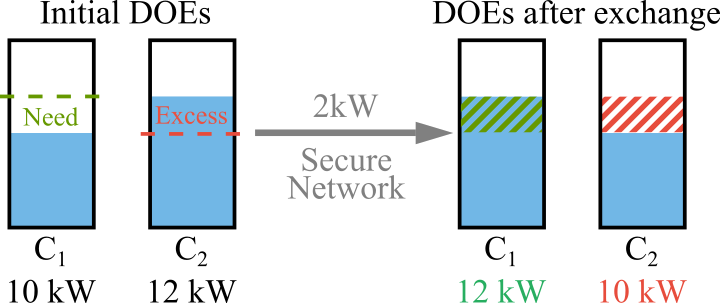

For example, suppose you want to charge your electric vehicle with a power of 12 kW for one hour, but you are limited by your limits to a maximum of a power of 10 kW. At the same time, your neighbor has some limits that they are not using. You both submit a buy and sell order. The market operator receives these orders, validates that the exchange respects network security, and confirms the exchange of limits: you can finally charge your electric vehicle without problems. This little example is represented in Fig. 2.

The key difference from other works is that this market does not trade electricity itself, but the right to use grid capacity. By embedding a security verification in the market-clearing process, the exchanges ensure that every trade keeps the network secure: no overloads, no voltage violations.

Why it matters:

By letting customers and businesses reallocate limits dynamically, it is possible to unlock underutilized value from existing infrastructure without complex management systems or expensive network investments.

The bigger picture:

As the energy transition accelerates, the real bottleneck is not generation; it is coordination. SecuLEx shows that the grid of the future can be both secure and decentralized.

This new operational paradigm — security through coordination — could redefine how we operate future grids.

Leave a comment