Gaspard Lambrechts, Damien Ernst and Aditya Mahajan

Access the paper: https://hdl.handle.net/2268/326874

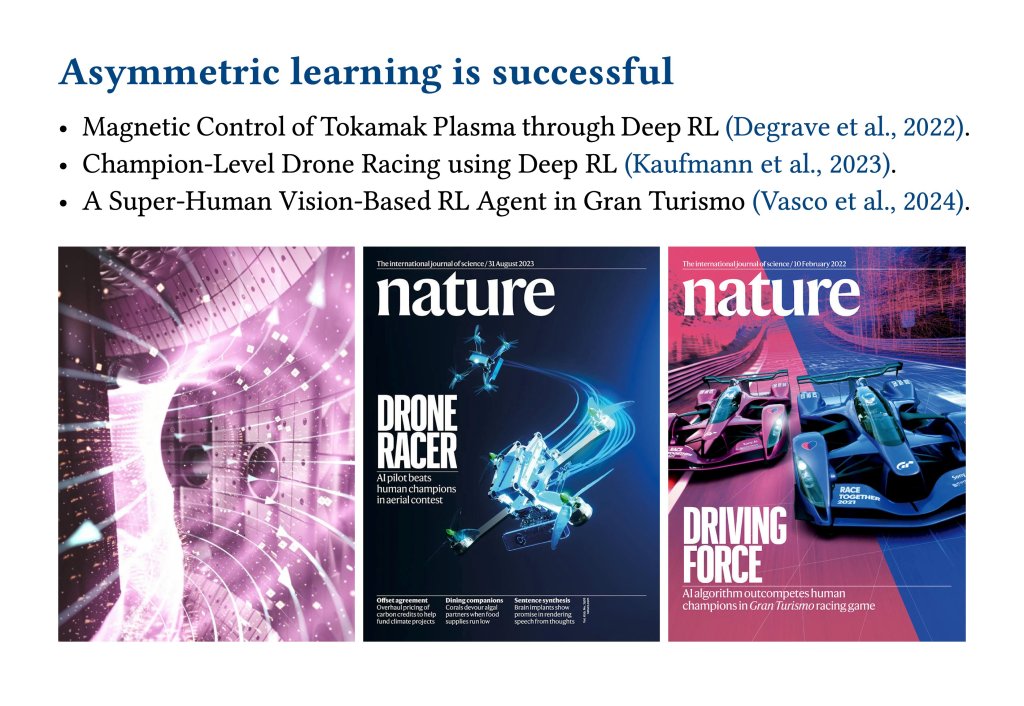

Our paper entitled “A Theoretical Justification for Asymmetric Actor-Critic Algorithms” was accepted at ICML 2025! Never heard of asymmetric actor-critic algorithms? Yet, many successful Reinforcement Learning (RL) applications use them. But these algorithms are not fully understood. Below, we provide some insights.

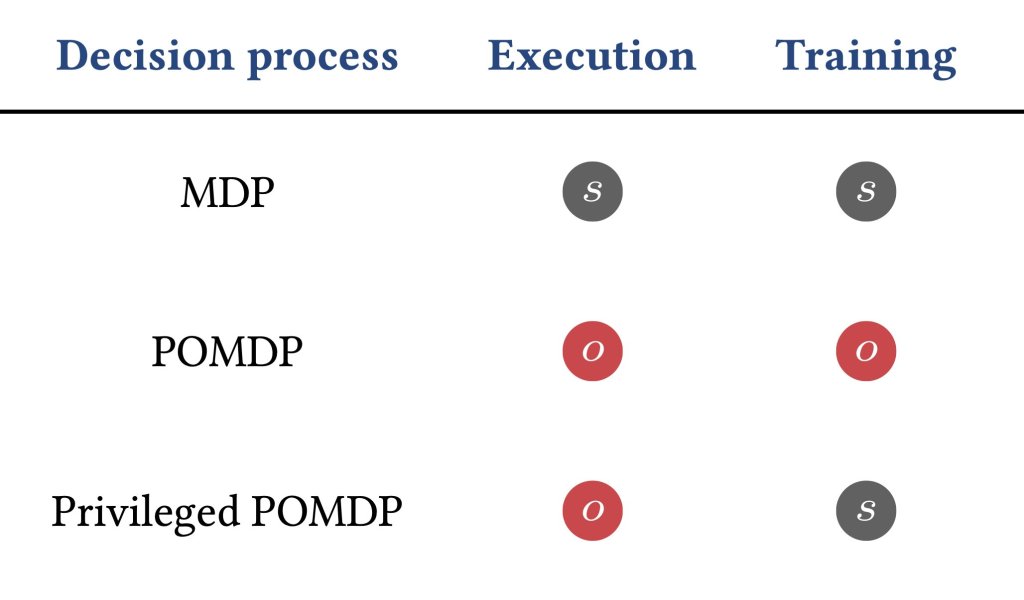

Typically, classical RL methods assume:

- MDP: full state observability (too optimistic),

- POMDP: partial state observability (too pessimistic).

Instead, asymmetric RL methods assume:

- Privileged POMDP: asymmetric state observability (full at training, partial at execution).

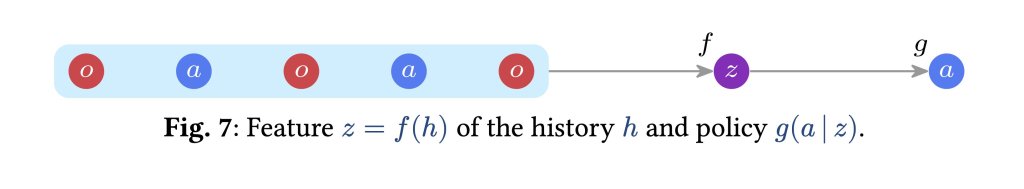

In a POMDP, we seek an policy π(a|z) that maps a feature z = f(h) of the history to an optimal action. In a privileged POMDP, the state can be used to learn a policy π(a|z) faster. Note that the state cannot be an input of the policy, since it is unavailable at execution.

However, with actor-critic algorithms, it can be noticed that the critic is not needed at execution! As a result, the state can be an input of the critic, which becomes Q(s, z, a) in the asymmetric setting instead of Q(z, a) in the symmetric setting.

While this algorithm is unbiased (Baisero et al., 2022), a justification for its benefit is missing. Does it really learn faster than symmetric learning? In this paper, we provide theoretical evidence for this, based on an adapted finite-time analysis (Cayci et al., 2024).

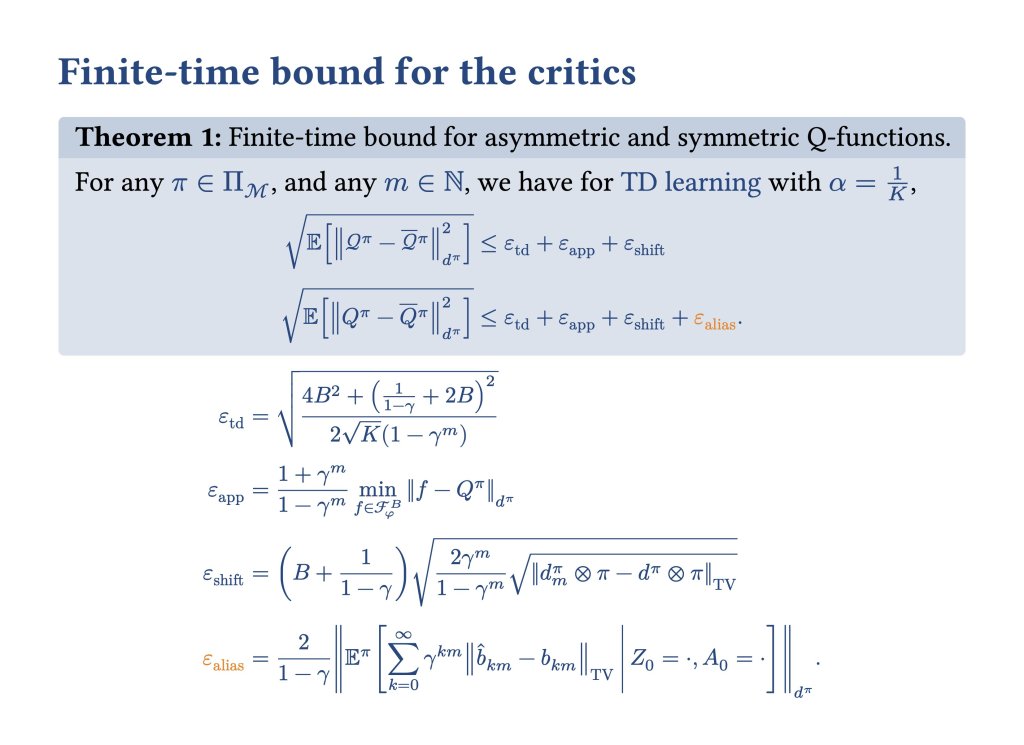

By adapting the finite-time bound from the symmetric setting to the asymmetric setting, we obtain the following error bounds for the critic estimates. The symmetric temporal difference learning algorithm has an additional “aliasing term”.

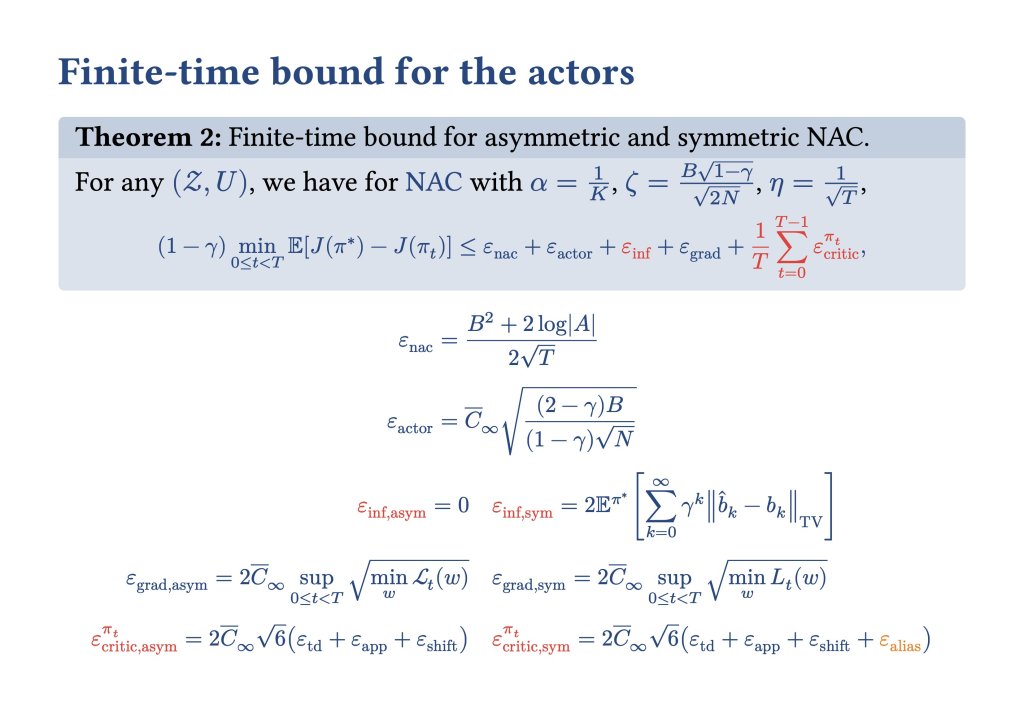

Now, as far as the actor suboptimality is concerned, we obtain the following finite-time bounds. In addition to the average critic error, which is also present in the actor bound, the symmetric actor-critic algorithm suffers from an additional “inference term”.

Thus, asymmetric learning is less sensitive to aliasing than symmetric learning. Now, what is aliasing exactly? The aliasing and inference terms arise from z = f(h) not being Markovian. They are bounded by the difference between the approximate p(s|z) and exact p(s|h) beliefs.

While this work considered fixed feature z = f(h) with linear approximators, we discuss generalizations in the conclusion. Despite not matching the usual recurrent setting, this analysis still provides insights into the effectiveness of asymmetric actor-critic algorithms.

TL;DR: Don’t make the problem harder than it is! Using state information during training is provably better.

Paper: https://arxiv.org/abs/2501.19116 or https://hdl.handle.net/2268/326874

Talk: https://orbi.uliege.be/bitstream/2268/326874/4/asymmetric-bound.pdf

Leave a comment